This is an opinion column.

This is the flip side, the uplifting Ying to the horrific Yang that angers us all: the senseless shootings, illogical deaths, maniacal wounding and killing of innocents, of people simply trying to live. Of children. Children robbed of their future. Children wondering, why did they shoot me? Because, dear child, folks are resolving their beefs—over money, over a man or woman, over revenge, over ego, over whatever—with guns.

A too-easily accessible, high-powered gun.

Because the cowards and punks, the baby shooters and baby killers, as Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin appropriately calls them, wantonly pull a trigger without a modicum of regard for whom a bullet may pierce. For whose heart, whose family it may shatter.

This is the flip side, too, of a wretched penal system labeled unconstitutional by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Like the 14 men in Birmingham standing on a stage recently—men who were paroled after serving time in Alabama prisons. Not all for violent or deadly crimes. For crimes, though, that often lead to worse, violent choices, deadly choices. Crimes that condemn lives to an inextricable cycle of hopelessness.

Fourteen men no longer about that life, men who don’t want to go back. And aren’t likely to. They’re among the men and women around the state who graduate from a rigorous multi-faceted re-entry program operating at 11 Alabama Bureau of Parsons and Paroles Day Reporting Centers (DRCs). A program that is accomplishing what most, if not all of us want: It’s changing people. Changing them, actually re-forming them with a disciplined, individualized—finally—approach that provides substance abuse/addiction and mental health treatments; attacks illiteracy; encompasses counseling for families and loved ones; trains participants in an employable occupation and puts them to work at companies in dire need of labor.

Puts them on a path toward a productive career. A productive life.

It’s the flip side of building prisons; it’s building people.

It changed Carlos Whatley. Less than two years after being released, after serving nearly 20 years for first-degree robbery, he drives a forklift at the Mercedes Benz plant near Tuscaloosa. He and his wife, who remained together through the incarceration, are awaiting the birth of their daughter. He was among the 14 on stage that recent afternoon. “I’m 40 years old now, and before I never even had a driver’s license,” he shared. “I have no intention of going back.”

After graduating from the statewide three-phase DRC re-entry program, formerly incarcerated Carlos Whatley (left) and William Terry are successfully employed and vow to never go back o prison. The program sees a recidivism rate of just 3 percent.

It changed William Terry, too. It’s been seven years since he was released after serving more than 12 years for unlawful distribution of illegal drugs. He was on that stage, a 49-year-old grandfather working three years now as a head cook at a fast-food restaurant where his girlfriend is the assistant manager. “I was living the wrong lifestyle,” he said. “I was always the black sheep, but God was always in my heart. I’m grateful for this program because it changed my life by changing my way of thinking.”

The program’s fiscal year ends September 30. As of FY 2021, the latest tally available, 301 formerly incarcerated men and women graduated from the program. Put a pin in that.

Semi-spoiler: They’re the flip side.

The program is under the wings of Cam Ward, a Republican and former three-term state legislator from Alabaster who has long been an advocate for criminal justice reform. Now, after being appointed by Gov. Kay Ivey in November 2020, he’s an evangelist for the DRCs. “Let’s get selfish here,” he says. “I can reduce recidivism and crime if I help someone deal with their underlying issues, train them with a real skill and get them a good paying job. We had a guy who went through the program, got a welding job starting at $87,000 a year. Three years later, he was making over $110,000. That guy is not going back to prison.

“It’s really common sense. It’s just pulling all the pieces together. We have a lot of the private sector say hey, we need to hire people, can y’all help get skilled labor? We can take care of that.”

Former state Sen. Cam Ward (center) oversees team leading 11 Day Reporting Centers for formerly incarcerated men and women. The program is seeing a recidivism rate of just 3 percent.

There are three phases: The first includes, but is not limited to, daily reporting to a center, a 7 p.m. curfew, mandated 12-step meetings addressing any substance and/or mental health needs, at least 40 hours of community service, family counseling, and five consecutive clean drug screens. Towards the end of this phase, participants begin undergoing ready-to-work training at J.S. Ingram State Technical College in Elmore County. “The only two-year college in the country that does nothing but provide job training for the formerly incarcerated,” Ward says.

The second phase begins with being connected with a potential employer. With Alabama’s unemployment rate at a historically low 2.6 percent, companies are running to the program to fill jobs. Participants must complete 90 days of stable employment, pay court-related penalties and fees, and continue therapy, treatments, and family counseling.

The final phase comprises six months of sobriety, clean random drug screens, continued full-time employment, GED classes as needed, and no major violations.

“The program is a holistic view of reentry,” Ward says. “I know that word gets used a lot, but it truly is holistic. We have a family reunification piece where we get with the family for therapy. We have family nights when we invite the family in and we review how the participant is doing—either well or what their challenges are. Our officers work very closely with the families.”

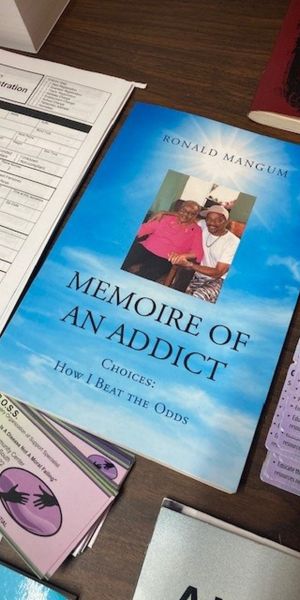

Some graduates have authored books chronicling their journey. On the day I toured the Montgomery, DRC their tomes are displayed on a table alongside flyers from companies hyping themselves as great places to work. In some rooms, participants were talking with a counselor. Other areas contained clothing and shoes for participants to use for job interviews.

Participants keep the DRC clean as part of their community service (“Saves the taxpayers,” says Bensema.) And take ownership of the responsibility. They’ll get miffed if someone spills, say, coffee in an area just cleansed.

“These are not ‘offenders’,” shares Rebecca Bensema, deputy director of parolee rehabilitation special populations and programs. “These are your neighbors. This is your classmate. This is your fellow parent at your kids’ school. That’s hard to swallow for some people. The general public sometimes forgets that when you’ve been incarcerated for 15-20 years, come out and have to fill out an application online, they don’t even know where to start.”

It’s been almost seven years since the first DRC opened in Birmingham in 2015, supported by a 2014 Second Chance Act grant ($687,186) from the U.S. Department of Justice. Also in 2014, the Alabama legislature passed the Justice Reinvestment Initiative and allocated $16 million from the state’s General Fund for bipartisan efforts to tackle inhumane prison overcrowding, inconsistent sentencing, and woefully resourced supervision of those released from prison.

Graduates of the re-entry program at 11 Day Reporting Centers for formerly incarcerated men and women have gone on to be authors. The program is seeing a recidivism rate of just 3 percent.

The latter was the most controversial of the elements because it emphasized supporting community-based programs rather than a singular approach under state guidance. Problem was many legislators were not even aware of the day reporting centers; Ward was among them. “What’s a DRC? Is what we said,” he recalls.

Legislators were oblivious to the DRCs largely because the leadership of the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles (it operates separately from the Board of Pardons and Paroles, which decides parole cases) was either all-in on providing social services or law-and-order types who espoused strict enforcement of parole conditions. Like sending people back to prison for, say, missing a parole officer appointment or failing a single drug test (which can easily happen when trying to escape the throes of addiction).

“Our agency was a pendulum,” Ward says. “Either you’re all law enforcement or all social services. We’ve had some directors who said. ‘No, no, no, no, I want all law enforcement,’ or they go back and forth. There was never a happy middle.”

He embraced the challenge of striking a balance—and overcoming skeptics. The current strategy was cobbled from best practices in other states, an unusual practice for a state where agencies rarely look beyond the way we’ve always done it. “We’re so siloed in Alabama,” says Bensema. The most intriguing model was Georgia’s DRC, which operates 16 full centers in highly populated areas across the state and 19 smaller ones in rural regions. They’re reporting recidivism rates (returning to custody within three years of release) of 4.8 percent among participants compared with 30 percent overall.

“Looking back at my terms in the legislature, they think the general policy with the criminal justice system is: Okay, go to prison, then you get this, this and this, and you’re done. That’s the problem. This model looks at individuals,” Ward said. “So, you may need a GED, some soft skills, and this and this, you may need mental health. You tailor it to the individual as opposed to a cookie cutter plan and I think we get more bang for our buck doing it that way.”

Here’s the bang: Alabama’s recidivism rate (measured by whether a person remains out of prison three years after being released) has long hovered at just above 30 percent–smack midway among all states. The rate for those who completed the program in 2018 is three percent.

Yes, three percent.

Like a pied piper, Ward waves that figure at former political peers all across the state. “Every chance I get I’m bragging to legislators, particularly my Republican brethren,” he says wryly. “I say, ‘You can’t be against this. Here’s what this does [regarding recidivism]’. For those skittish on sentencing reform, when you tell them this and say, ‘This will reduce crime if you invest in it,’ They say, ‘You’re right, it’s hard to go against that, hard to beat that. I’m all for that.’”

All for the flip side.

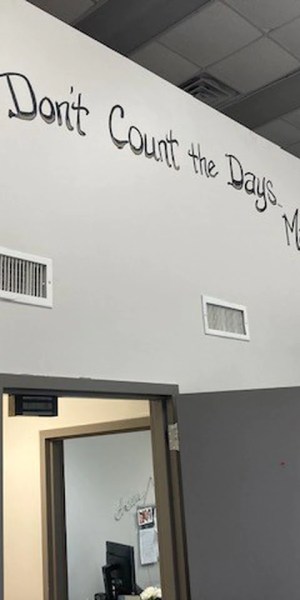

A mural inside the lobby of the Montgomery Day Reporting Center, one of 11 DRCs across the state with a holistic re-entry for formerly incarcerated men and women. The mural was painted by a participant. The program is seeing a recidivism rate of just 3 percent.

Don’t Count the Days. Make the Days Count. Those words are colorfully scripted above the door beyond the lobby at the Montgomery DRC. They were painted by a participant in the program’s partnership with the Alabama Arts + Ed project at Auburn University. “It assists our participants in working through trauma,” says Bensema. “You would be surprised at how much art can help when you can’t verbally articulate what you’ve been through in the prison system and even growing up. A lot of them grew up in poverty and in areas that were not great or stable. Being able to work through that is integral to then being able to become a productive member of society and to be stable.”

“Everybody goes through something in life, it’s just how you deal with it.” That’s William Terry, after the graduation. “The man I am today thinks things through. I don’t allow myself to go around old crowds—just work and take care of my family.”

Terry suffered from substance abuse and accessed both addiction treatment and health services. “It helped me realize where I was, I didn’t have to stay there,” he said. “They just allowed me to be myself. I had to learn how to communicate with others because prison is a whole ‘nother life—just learning how to open up ‘cause in prison you’re closed in. You don’t have an opportunity to be yourself. You’re more to yourself than anything.

“I’m a very emotional person now when it comes to speaking about how God allowed me to go through things. I’m not ashamed. I’ve been at my lowest and I might not yet be where I need to be. But I’m grateful I am where I am. It’s just been a long journey.”

He shares the journey with his grandchildren. “I share my path,” he said. “I share the old me and the new me with them because they need to know all of it, not just part of it. My kids see my growth. I just thank God my grandkids didn’t have to experience that. When they get older, I will tell them about it that’s a part of their grandfather’s life. They need to know their grandfather’s life, not just the good things, but the struggle life will take.”

“Down end” is how Whatley describes the north Birmingham Evergreen neighborhood that raised him—raised him after his father died when his son was 11 years old. “I had to learn my way,” he shared, “I was easily swayed by what was going on in the neighborhood. It wasn’t too much positive, if none at all. I was easy to latch on to the negative influences.”

The mental health services, he says, were the most valuable aspect of the program. “I never really believed in it,” he said. “Didn’t believe somebody who didn’t know me could help me with my problems.”

Whatley was married when he entered incarceration and the couple remain together, though both struggled through the separation. “I appreciate her more seeing her personal growth and development. She found ways to better herself. She took our tragedy and turned it into a triumph.”

Now, after shifts at Mercedes Benz, he revels in watching his six-year-old son learning his way. “It’s tickling me to see him think of something and try to put it to fruition.”

Ward says he attends all of the graduation events and calls them the “highlight of my career.” Indeed, he beamed like a proud uncle throughout the ceremony in Birmingham, “We can talk about policy, politics, and high-minded issues, but seeing those men succeed today is what it’s all about.”

With state unemployment at historic low (2.6 percent). the private sector is eager to hire graduates from the this program under the Bureau of Pardons & Paroles, which is drastically reducing recidivism.

In April, the bureau launched the Probation and Parole Reentry Education Program at a facility in Perry County that had long languished under the Department of Corrections. It’s the first residential facility to host the same program currently utilized at DRCs and will house 250 men.

“Perry County is going to be kind of a game changer because it holds vastly more people than what you have at the DRCs and it’s way more intense because it’s residential,” Ward says. “My goal would be to have these DRCs in every corner of the state, in every community so there’s no way we send someone back to a rural or impoverished area and they go: Well, I can’t get there. I would love to see us get to like 25 or 30. So that everyone has an opportunity to get this kind of service.”

An opportunity to be re-built, to become part of the flip side, to embody a solution we all desperately crave.

More by Roy S. Johnson

MAGA whining about Biden proves Trump 2024 is dead

World Games’ $14 million debt indeed ‘sucks’, city council’s anger did not

KKK image used by GOP county chair may have been an ‘error,’ it was not a mistake

Black pastor arrested for watering flowers: ‘God will work it out for me’

When Bill Russell stopped blocking my shot

The future of the Magic City Classic? It’s a no-brainer

Roy S. Johnson is a 2021 Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary and winner of 2021 Edward R. Murrow prize for podcasts: “Unjustifiable”, co-hosted with John Archibald. His column appears in The Birmingham News and AL.com, as well as the Huntsville Times, the Mobile Press-Register. Reach him at rjohnson@al.com, follow him at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj.